Mobilia Magazine 1994

The Double Life of Walter Miller

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

THE DOUBLE LIFE Of

WALTER MILLER

The Museum of Automobile History is the Brainchild of Automotive

Literature Dealer Walter Miller

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

STORY BY J.M. FENSTER

Photos by Michael J. Okoniewski

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

n

I rivers do a double-take when they

^M pass a certain neat, if homely,

^^V building off Carrier Circle in

^^ Syracuse, New York. They might be catching a better look at the shiny silver biplane on the front lawn: a Hollywood movie prop from 1933. Or perhaps it’s the red car in the parking lot, with a front at both ends, like a two-pointed pencil. Or maybe the trio of bantam trucks, none of which looks like it could haul anything larger than, say… a sales brochure for a 1930 Maybach.

If the place gets its share of attention from passersby, it’s just as well, because the building happens to be the headquarters of Walter Miller Automobile Literature.

No one sells more automobile literature than Walter Miller. Before he can sell it,

|

though, he has to acquire it, so Miller measures the growth of the business in terms of file cabinets. Three-drawer file cabinets hold his inventory: the original brochures and owners’ manuals that constitute the bulk of his sales. Miller vividly remembers the great day when he needed to purchase his first, sole file cabinet; that was in 1978. Today, there are 300, and he has taken to adding them 25 at a time.

Over and above the automobile literature—quite literally—Miller’s building is full to the brim with other automo-bilia: posters, toys,

|

games, models, souvenirs, clothes, accessories, letters, autographs, ashtrays, licenses, buttons, signs, pennants, and flags. All of it pertains to the 100-year history of the automobile in America and around the world—

|

||

|

|

||||

|

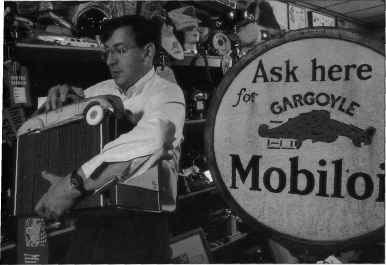

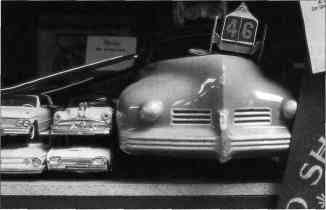

Left: Miller carries a load of recently acquired items past a landscape of automobilia in his Syracuse, New York shop. Above: A sampling of toys shows both the lighter side of America’s obsession with the automobile—and the lighter side of Walter Miller.

|

|||

|

but none of it is for sale. What started as a collection has emerged as a dream for Walter Miller: the Museum of Automobile History.

Miller’s museum will open in Syracuse in 1995. "I want it to appeal to every person," he says, "especially groups from schools. They’ll see the automobile era chronologically, decade by decade, and see it through thousands and thousands of the actual, original things that were part of it." The museum will include memorabilia pertaining to autos, trucks, and motorcycles, with America, Europe and Japan all represented.

In Miller’s view, "the automobile has

|

||||

|

Continued on p. 40

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

M 0 B I L I A OCTOBER 1994 39

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

F I A 1 B I I

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Continued from p. 38

|

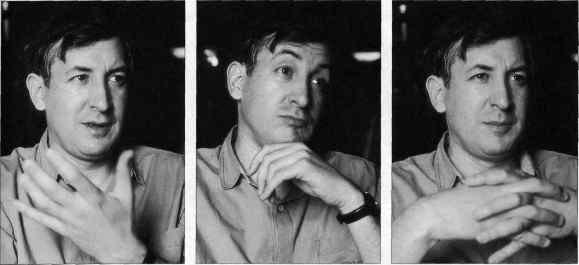

Walter Miller is passionate about the hobby which has

become his vocation."! want the museum to appeal to

every person,"says Miller. "They’ll see the automobile era

chronologically, decade by decade, through thousands of

the actual original things that were part of it." Below:

With offerings like these, the museum is sure to please

both enthusiasts and the general public.

|

reminders like, "The other driver is blind for a half-mile, unless you dim your lights." (Another poster, for an auto thrill-show, seems to diminish that alarm, however: "France the Magician will drive an automobile blindfolded!") The safety theme continues with a framed selection of speeding tickets issued to F.T. Sanford, a noted aviator, by English police in the years around 1906; one time, for example, Sanford was nabbed for going 20 m.p.h.

The automobile was a monumental invention, and it inspired others—others very nearly as important, such as the Car-B-Cue, a handy appliance that cooked hot dogs in the car by plugging into the cigarette lighter. Another of Miller’s car accessories is the Thermador, an elemental air-conditioner from the Fifties that worked by hanging from the car window. Outside air blew through the ice-filled Thermador, and then flowed coolly into the passenger compartment. Another sure thing that just didn’t catch on was a propeller that—for some reason which remains unclear!—attached to the front of the car.

In most cases, it is a compliment to call a collector "discriminating." Walter Miller, however, has drawn only the loosest boundaries around his collection, accumulating anything that mankind created in the wake of the automobile. From patent models to four-door pin cushions, what Miller likes about original automobil-ia is—everything.

Walter Miller’s Museum of Automobile History may or may not display a few actual automobiles —

Continued on p. 42

|

|||||

|

altered our society to a greater extent than any other invention since the wheel." The museum will demonstrate this, one item at a time.

Over 10,000 pieces constitute the collec-.on, and many are one-of-a-kind. At least one hopes so, in the case of a hand-lettered canvas sign that hung on the side of a car in the mid-Twenties: "My advice—Don’t buy a Gray Car. This one is absolutely no good." It continues with a long list of specific complaints. (One doesn’t see many Gray dealerships anymore, come to think of it.)

Other of the one-of-a-kind items are slightly more august. In 1919, Ettore Bugatti wrote to the Duesenberg brothers in New Jersey, and that letter is now part of the collection, along with hundreds of other automotive autographs and letters. Miller is especially interested in the Japanese auto industry in the postwar era and thinks he may well have more material on it than anyone, anywhere. One of Miller’s framed letters, received by the Ford Motor Company in 1948, requested "automobile and trucks [sic] catalogues and anything likely to interest us." It was sent by Toyota.

Stylists’ renderings from the ‘teens through the Sixties depict cars that might have been: a 1949 Cadillac sports car, for example. The hundreds of original renderings also include work from the great carrosseries of Europe, such as Kellner, Saoutchik, and Figoni

|

|||||||

|

and Falaschi.

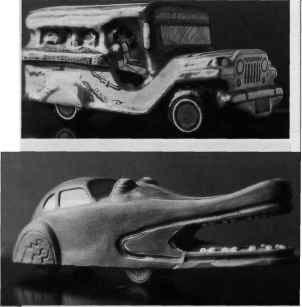

Many collections aspire exclusively to such pur-sang, and the rarefied company of Bugatti or Saoutchik. Miller, however, fills out the entire picture of automobile history by paying the same respect to the most humble pieces (which, ironically, can now be just as rare). He delights in his growing collection of homemade, folk-art toy cars; crude as many of them are, they reflect automobile enthusiasm at its most sincere level.

Just as basic are the posters and enamel signs that advertised road safety, with

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

n n t n a c o

|

u n b i i is

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

[ i I I I I I

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

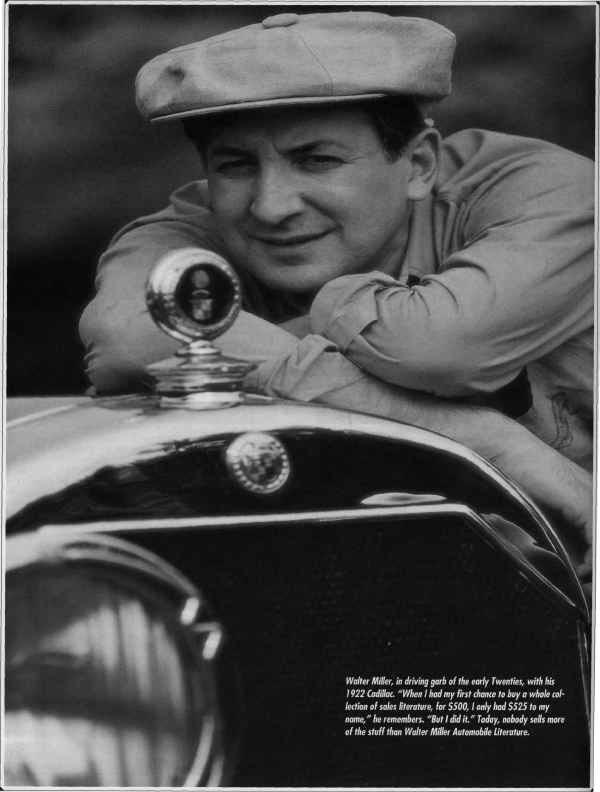

up the corporate ranks at General Motors. But he didn’t. The summer after graduate school, Miller surprised his friends, relatives, and himself by plunging full-time into the business of dealing in automobile literature. "All I had was a few banker’s boxes of stuff," he says, "and when I had my first chance to buy a whole collection of sales literature, for $500, I only had $525 to my name. But I did it." At the time, in the mid-Seventies, the late

|

||||||||

|

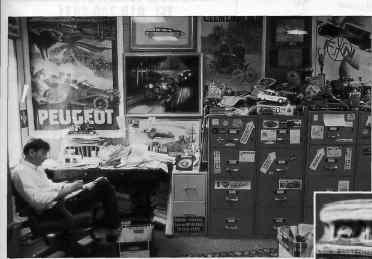

In the splendid chaos of his memorabilia-crammed offices, Walter Miller pores over auto literature. A few of his 300 jam-packed file cabinets stand by.

|

father was not a car guy," he says, "but he had a copy of Floyd Cly-mer’s Those Wonderful Automobiles and I read it when I was five. It sparked my interest." Later, when young Wally began to collect old magazines, like Fortune and The Saturday Evening Post, he ripped out ads for some of the cars described in Cly-mer’s book. With that, he started on the road to both his

|

|

|||||||

|

Continued from p. 40

|

|||||||||

|

Miller hasn’t quite decided yet. Actually, though, they might seem extraneous. Plenty of other museums show automobiles; this one will be unique in its attempt to show the world as it grew up all around the automobile. Walter Miller has been dealing in automobile literature for 25 of his 40 years. He has been a collector for 35, but it wasn’t always cars that caught his eye. As a boy, growing up near Syracuse, he liked to collect stamps, coins, seashells, and baseball cards. "My

|

|||||||||

|

business and the museum.

As a

teenager, Miller earned pocket money selling car ads at local car shows. He earned business degrees at the State University of New York at Bing-hamton and McGill University. By then, he assumed he would go to Detroit and work his way

|

Two colorful examples of automotive folk art show auto-mobilia at perhaps its humblest but most sincere level.

|

|||||||

|

Nat Adelstein was the biggest literature dealer in the country. "That gave me the inspiration that my business could grow to be big," Miller recalls, "but it took a long time to build it, and even to learn how to build it." It took him two years of hunting just to find enough material to fill that first file cabinet.

The acquisitions of three major collections are the milestones of Walter Miller’s expansion. Every year from the early Thirties to the Sixties, a Ford executive named McCullough kept abreast of styling in the worldwide industry by ordering complete sets of brochures. His material, which filled two vans, was Miller’s first major purchase. The second one brought an old circle to a close, as Miller bought the Floyd Clymer research

|

|||||||||

|

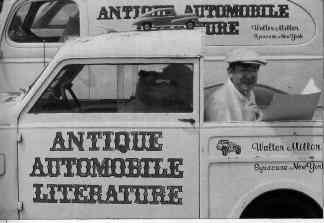

Time for a bit of homework in the bed of Miller’s bantam pickup.

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

flPTflDED 100/1

|

u n b i i i s

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

I I i I I E 1

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

library from the publisher’s estate, including over 50,000 photographs. That filled half of a tractor trailer. The third collection acquired by Miller was that of J.L. Elbert, the author of a fine Duesenberg book, The Mightiest American Motorcar. For five decades, Elbert had made a hobby of sending away for automobile literature; he was so meticulous that he even kept the envelopes in which the material arrived. The Elbert collection, 120,000 pieces in excellent condition, filled an entire house.

In the early days, Miller conducted most of his dealings at automobile shows; today, his is a mail-order business and

|

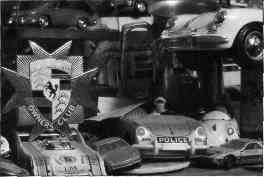

Toys and die-cast miniatures in every size and shape—and in every corner of Miller’s building.

|

Henry Leland to lose control of his company, and for Henry Ford to take it.

Such momentous artifacts are in stark contrast to such whimsical items as an original watercolor, circa 1915, of three vegetables riding in a touring car. Where does it fit in the scheme of automobile history? It is enough just to wonder why the potato got to drive.

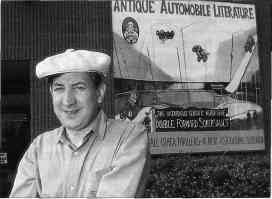

Humor runs through Miller’s museum collection in the form of countless gags and goofy items inspired by the car. On the outside of the building, Miller commissioned a local artist named Jeff Davies to paint a billboard poster advertising Miller in

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

From plates, to automotive art, to signs, a wealth ofauto-mobilia awaits its new home: the Museum of Automobile History opening next year in Syracuse, New York.

|

ed to specific subjects,

|

Miller with mock circus poster by artist Jeff Davies, depicting the "Hazardous Terrific Automobile Double-Forward Somersault." And for his next trick… The Museum of Automobile History!

|

|||||

|

answer mail, fax and phone queries, and pack items for shipment.

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

he sets up at only two shows: Hershey and Carlisle. The company advertises extensively, especially in search of material with which to fill file cabinets. Miller usually has several pre-1900 pieces on hand. One example is a Duryea catalogue from 1898 that lent perspective to the young auto industry by depicting its own outmoded 1893 models.

At present, Miller says that literature for sports cars from England, Germany, and Italy is in growing demand, along with that for Mopar cars from the Fifties, and for early Japanese cars. The steadiest interest over the years has been in material related to Corvettes. Ten employees in the Syracuse building sort the literature, prepare lists relat-

|

All around the employees as they perform their tasks, museum items have been piled, stacked, arranged, balanced, and otherwise safely stored. While Walter Miller is in the process of selecting a site in central New York, the rooms of his business have become a de facto museum for auto fans and historians.

Even in disarray, far from the sensible order that Miller intends to give the collection in its permanent site, the bits and pieces convey a dimension of social history. One compelling item is a framed letter from the Detroit Trust Company, dated December 9, 1921, that begins "We have today been appointed receiver for the Lincoln Motor Company…" With that, the die was cast for

|

a circus feat: "the hazardous terrific automobile double forward somersault.

"Out thrilling all others," the poster continues, "a new astounding sensation." That might actually serve to describe Miller’s newest and best act: the Museum of Automobile History.

All photos © 1994 Michael}. Okoniewski.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

M 0 B I L I A OCTOBER1994

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||